On January 20, 2025, President Trump’s first day of his second term, the president signed an executive order to withdraw the United States from the World Health Organization (WHO), a promise he had made toward the end of his first term.

That promise, of course, had been delayed: before a withdrawal could take place, incoming President Biden reversed Trump's order on the first day of his presidency.

Within a year, the Biden administration proposed a set of amendments to the WHO's International Health Regulations and called for the creation of a Pandemic Treaty by the WHO.

But now, four years later, President Trump revoked his predecessor's reversal, ordering an immediate halt to US negotiations on the Pandemic Treaty and rejecting the 2024 amendments to the International Health Regulations.

On signing the executive order, Trump said, “World Health ripped us off, everybody rips off the United States. It's not going to happen anymore.”

A full withdrawal from the WHO is expected to take one year.

Why should we leave the WHO?

As Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said in a video recorded in 2023, “The World Health Organization was once a great agency that took care of the poor and underserved communities around the world. But in recent decades, it’s been taken over by global elites and foreign powers that don’t have America’s best interest at heart.”

Kennedy is right: the WHO is a shadow of its former self, now controlled by forces that want, among other things, to use the fear of pandemics to centralize global health decisions and ultimately rob Americans of their freedom to make medical decisions that crucially impact their lives.

That, in brief, is why we have to and should leave the WHO, and why it’s fine that we are not voting in May on the WHO’s latest “pandemic preparedness” agreement – proposed, agreed on, and expected to be signed into law by many member states without U.S. involvement.

But the WHO wasn’t always as it is now.

Why has the WHO become so controversial?

The World Health Organization, part of the United Nations system, was formed at the conclusion of World War II to improve global public health. In its early years, the WHO performed well. For example, the WHO coordinated international efforts that led to vanquishing smallpox in 1977. However, an expensive 37-year effort to end polio, begun after its success combating smallpox, has so far failed.

Even before COVID, other WHO efforts have been widely criticized.

2009 Swine Flu

In 2009 the WHO declared a “phase 6” swine flu pandemic. Few people were aware that the WHO had mediated “sleeper” contracts between the US, many other nations, and pharmaceutical companies. The contracts were for hundreds of millions of doses of vaccines, which would have to be invented, produced and purchased when the WHO Director-General declared a high threat pandemic, termed “phase 6.”

However, what people discovered was that the WHO’s definition of a "phase 6" pandemic had been changed a few weeks before the 2009 declaration–removing language that required "enormous numbers of deaths and illness." The change allowed the WHO to declare a phase 6 pandemic for any minor respiratory illness, as long as it involved a new virus. And each winter there are new viruses.

The WHO’s declaration obligated WHO members to purchase billions of dollars of vaccines. Furthermore, the WHO “experts”calling for the declaration turned out to have financial conflicts with the vaccine manufacturers. And then the pandemic turned out to be no more serious than an average year's flu, for which most nations do not recommend vaccinations. One brand of these rapidly-produced injections (Pandemrix) led to over 1300 cases of severe narcolepsy in adolescents.

2014 Ebola

When the world's largest Ebola outbreak occurred in West Africa, according to NPR,

"At first the agency that's responsible for providing leadership on global health matters" was dismissive of the scale of the problem in West Africa. Then it deflected responsibility for the crisis to the overwhelmed governments of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. After eight months, it finally stepped up to take charge of the Ebola response but lacked the staff and funds to do so effectively."

2018 Ebola

When the world's second largest Ebola epidemic occurred in East Africa several years later, the WHO's failures were even more profound. It delayed responding for nearly a year. Despite the new availability of drugs and vaccines, the epidemic had a mortality rate of 66% – the highest ever for Ebola. WHO's coercive efforts to keep local populations contained were so unpopular that there were over 300 physical attacks on healthcare workers and health centers.

Can the WHO be Reformed?

Responding to criticisms, WHO has long promised reforms, but they haven't materialized. Most recently, most of WHO's COVID recommendations lacked any scientific justification and caused huge damage, as countries everywhere adopted them in lockstep.

Yet a promised review of WHO's COVID performance resulted in a report by WHO insiders urging more of the same measures next time.

The WHO budget

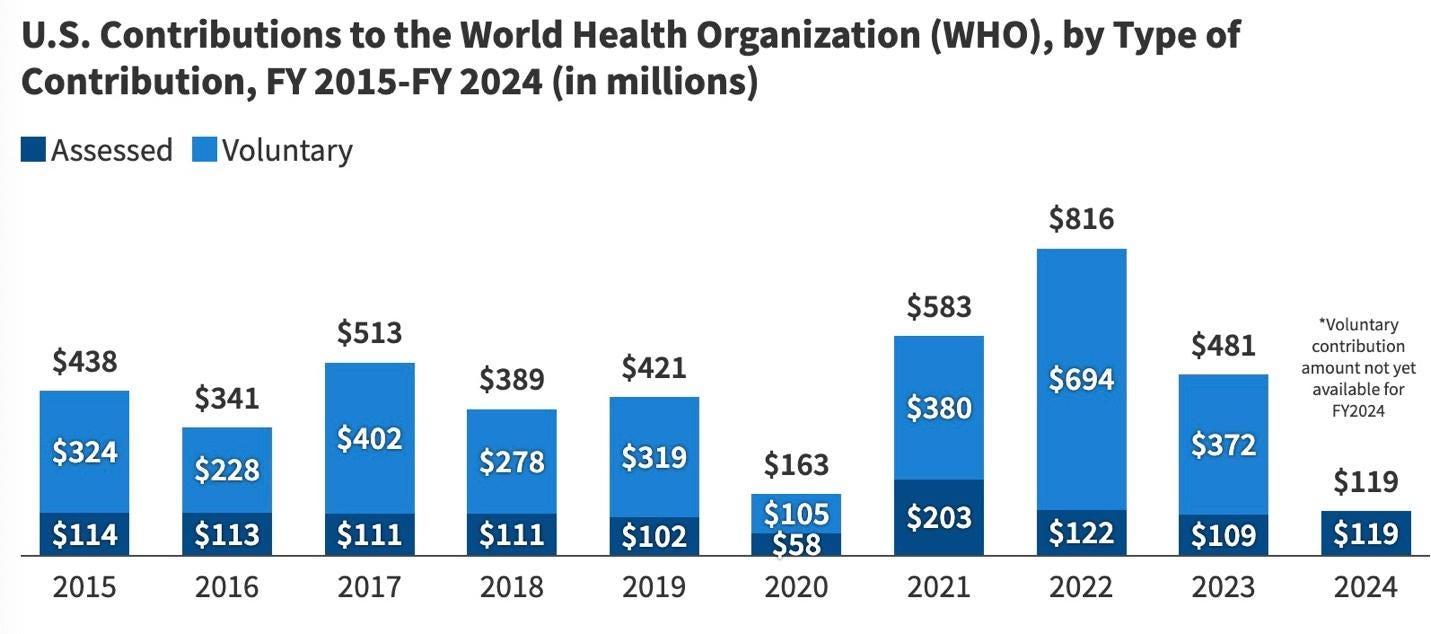

As the WHO budget increased over time, the agency switched from relying on dues for most of its funding, to relying on donors. Currently, dues make up only 16% of the WHO budget and donors (nations, foundations, pharmaceutical companies) supply the rest. Seventy-five per cent of the WHO budget is spent on projects and materials chosen by donors. Only 25% of WHO's funding is discretionary.

Unsurprisingly, the WHO has come to dance to the tune of its donors. Until now, its top donors have been the US, UK and German governments and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF, now the Gates Foundation). The Gavi Alliance, founded and heavily funded by Bill Gates, is another major donor to WHO. If you add Gavi's contributions to the BMGF contributions, Bill Gates has been the WHO's largest contributor. The graph below shows the WHO's funders during 2022-2023.

The US' dues and donations for the past decade are shown below. A US withdrawal from WHO is expected to cost the WHO $958 million dollars over the next 2 years.

The Pandemic Treaty and International Health Regulations amendments

In 2021 a group of Prime Ministers, led by the UK's Boris Johnson, called for a new Pandemic Treaty to: "build a more robust international health architecture that will protect future generations… The Covid-19 pandemic has been a stark and painful reminder that nobody is safe until everyone is safe… Immunization is a global public good and we will need to be able to develop, manufacture and deploy vaccines as quickly as possible."

The Prime Ministers who signed the call included a number of the World Economic Forum's Young Global Leaders, including Angela Merkel of Germany and Emmanuel Macron of France. The WHO Director-General also signed, and the WHO created a committee to draw up the treaty, with a goal for adoption at the annual meeting of WHO's member states in May 2024.

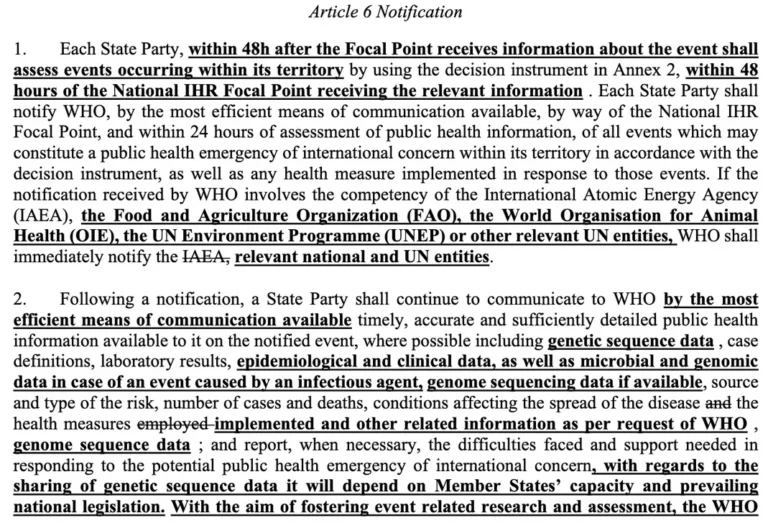

Meanwhile, the U. S. proffered a set of amendments to the International Health Regulations along the same lines. Then all WHO members were encouraged to submit proposed amendments.

The justification for these two documents was said to be the need for health equity – getting drugs and vaccines to less developed countries quickly and fairly during future pandemics; and the need to improve on pandemic management and avoid the mistakes of COVID-19.

What were the two treaties really meant to accomplish?

When you read the fine print in each document (both are treaties), it turns out that they provide neither equity for poor nations nor actual improvements to the pandemic response. Instead, their main purpose was to centralize control of international public health emergencies in the WHO.

The WHO Director-General would be able to declare a public health emergency at will, with no specific requirements. This could be an infectious disease emergency, a climate emergency, firearm emergency, or anything that had the potential to impair health in more than one country.

Once an emergency was declared, the Director-General would then direct nations regarding what they must do and what they would be prohibited from doing. He could mandate vaccinations, tests, quarantines, close borders–but also have the power to restrict access to medications that he deemed "excessive."

The draft treaties further demanded that nations perform surveillance of their citizens' social media presence to censor misinformation. The WHO would also expand surveillance for infectious disease outbreaks by collecting everyone's medical records.

Vaccines would be rapidly developed for outbreaks, but not licensed, since proper testing would take too long. Their manufacturers would be given a liability shield.

Finally, WHO proposed to set up a lab network and become a pandemic pathogen lending library.

Nations were asked to seek out potential pandemic pathogens (a.k.a. biowarfare agents), sequence them, send the WHO samples, and the WHO would share them with researchers globally. If a potential pandemic pathogen led to development of a drug or vaccine, the nation that provided the pathogen would receive unspecified royalties and gain access to some free and reduced-price pharmaceuticals. But there was no "equity" for nations that did not supply pathogens and only limited "equity" for those that did.

The treaties were in fact counterproductive, creating a legal mechanism to impose all the horrors of COVID pandemic management on the world at the will of the WHO. Doctors already know how to deal with pandemics, using established methods and repurposed drugs – and it is not by obeying one-size-fits-all, top-down edicts.

While the WHO's proposals were concerning, they were also unconstitutional, flying in the face of the 1st, 4th and 10th Amendments of the Constitution. They quashed human rights and supplanted the domestic laws of the WHO's member states.

What the WHO was doing was to create a new, global governance structure under the guise of managing public health and complying with Agenda 2030. What the WHO never publicly revealed was that carrying out this agenda would cost ten times as much as the current WHO budget. Nor did WHO say where that money would come from.

You did not see any news about this project in the mainstream media. It was all done very quietly.

We dodged a bullet

Realizing this dire threat, a huge upswell of angry and committed citizens in the U.S. and overseas got educated and got to work. They demanded their elected officials reject the WHO proposals.

And so last May, 49 U.S. Senators told President Biden to stop negotiating the treaties, and if the Pandemic Treaty passed, that it would require Senate ratification by a two-thirds majority. Then 26 Governors refused to allow the WHO any jurisdiction within their states, and 22 Attorneys-General took a similar stand. All were Republicans. Finally, two states, Louisiana and Oklahoma, passed laws asserting that neither the WHO, United Nations nor the World Economic Forum could have any authority in their states.

This had a chilling effect on passage of the two treaties. At the annual 2024 WHO meeting, a greatly watered-down version of amendments to the International Health Regulations passed, but the Pandemic Treaty failed. Despite continued and frenzied attempts to get a new Pandemic Treaty adopted before President Trump took office, it didn't happen.

But on April 16, absent the US, WHO negotiators finally came to consensus on a Pandemic Treaty. While many of the worst provisions were removed, the Treaty provides a framework for increasing centralized control, over time.

President Trump punched back against a globalist power grab, which tried to use the fear of pandemics to gain WHO authority over all things affecting global health. In his role leading the Department of Health and Human Services, Kennedy will finish the job of extricating us from WHO, while bringing back to Americans the freedom to choose their own medical care, always.

World health governance by a central authority is now off the table for the US – hopefully forever. But not for the rest of the world. The struggle continues. The treaty will be voted on by WHO members at the end of May.

Meryl Nass, MD, is a physician who founded Door to Freedom to fight the WHO coup. Her medical license was suspended for treating patients with repurposed drugs during COVID and issuing warnings about COVID vaccines.

Published by The Kennedy Beacon