What decision-making role will the Australian parliament have in relation to the proposed IHR amendments?

This is a repost from Libby Klein’s substack, Reclaim Ethical Medicine

None, actually. Complacent Australians who think parliament will be asked to pass legislation to implement the IHR are sadly mistaken.

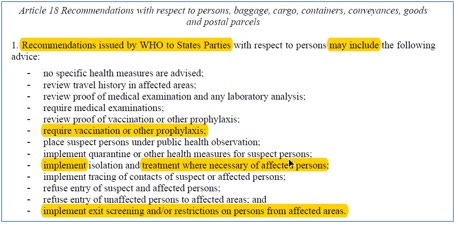

There’s a debate raging about whether proposed amendments to the International Health Regulations (IHR) will involve countries such as Australia ceding sovereignty to the World Health Organisation (WHO). We’ve heard lots of platitudes, for example from Senator Gallagher who claimed in the Senate in December 2023: “Let me be clear that the proposed treaty will not undermine Australia’s sovereignty in respect to health policy and will not operate to prevail over Australian law.” But substance of the amendments to the IHR is plain, and simple, actually: Australia will be obliged to follow the WHO’s “recommendations” in relation to public health, in the event of a public health emergency such as a pandemic. We can see this in black and white in the proposed amendments to Articles 1, 13A, 42 and 43 of the IHR. Yes, it will be Australia making the decisions, but we will have given the WHO the legal authority to tell us what those decisions should be. You can argue ’til the cows come home whether that’s “ceding sovereignty” but I ask you: why would an Australian government want to put us in the position where we are legally obliged to follow the WHO’s “recommendations” in the first place, noting that the list of (binding) recommendations in Article 18 includes – but is not limited to – mandatory vaccination, isolations, medical treatment and restrictions:

If you’re wanting to believe that all is well, you might take comfort in the idea that our parliament would have to pass any necessarily implementing legislation. But it turns out that sections 477 and 478 of the Biosecurity Act 2015 already give the government power to make public health orders in order to implement World Health Organisation recommendations, even if this is not required for public safety of Australians. So there’s no legislation that needs passing in order for us to implement this power transfer into Australian law.

The government’s Explanatory Memorandum for the Bill which became the Biosecurity Act 2015 clearly states the intention was to enable Australia to comply with our international legal obligations including the International Health Regulations:

Now that “recommendations” are to become binding, Australia finds itself in the bizarre position of its parliament having to pass legislation in order to avoid becoming indentured to the WHO. This is a magic trick! It’s not just that no legislation needs to be passed by the Australian parliament, for Australia to become legally bound to follow the WHO’s binding public health recommendations during a pandemic. On the contrary, Australia’s parliament would need to proactively amend the Biosecurity Act to remove the power to follow the WHO’s recommendations. (Or take the simpler approach of just rejecting the IHR amendments in the first place to avoid the problem.)

If there’s no handbrake there, maybe parliament will at least decide whether we accept the amendments which make the WHO’s recommendations binding? Ah, no. The government of the day has the authority under s61 of the Australian constitution to make decisions in relation to treaties such as the IHR amendments. We are reliant on the Joint Parliamentary Standing Committee on Treaties (JSCOT) to scrutinise the proposed amendments.

Will JSCOT do the job? When Alexander Downer, then Minister for Foreign Affairs, announced the establishment of JSCOT in 1996 he said it would “provide proper and effective procedures enabling parliament to scrutinize intended treaty action” and “overcome what this government considers to have been a democratic deficit in the way treaty-making has been carried out in the past”. But JSCOT has not lived up to expectations, and has been described by academic commentators has having become “a tool of political management, a means by which the government could channel protest, deflect opposition, and in essence legitimize its own policy preferences.”[1]

Perhaps this is not surprising given that under JSCOT’s terms of reference a majority of members are government ministers.

Members of JSCOT – led by Chair Josh Wilson – carry a heavy burden in relation to the IHR amendments.

Their task is to understand the changes – requiring significant investment of time and energy – and then to give frank and fearless advice to the government and the people of Australia. They need to conduct an inquiry which educates their fellow parliamentarians and the public at large as to the true nature of the proposed changes. They need to deliver a strongly worded recommendation to reject the proposed amendments.

The key question JSCOT must get onto the public agenda is: do you support a government which wants to outsource public health decisions to the WHO?

When the IHR amendments are tabled mid-2024, they will be accompanied by the Federal government’s National Interest Analysis (NIA), a recent example of which can be found on the JSCOT website. Perhaps the NIA for the IHR amendments will answer some key questions. If not, we can only hope the (yet to be announced) JSCOT inquiry and the wider electorate agitate these issues to the point of obtaining proper answers from the government:

1. Why does the Federal government want to hand decision-making over to the WHO?

2. If the Federal government doesn’t intend to comply with binding WHO public health “recommendations”, why is it supporting the power transfer? What would the sanctions be for non-compliance? (See here for a good discussion of the likely influence of the amendments despite the lack of formal enforcement mechanisms.)

3. If the government does intend to comply, why?

4. How is committing to complying with future WHO legally binding “recommendations” in Australia’s national interest?

Thinking Australians will not be satisfied with a glib answer along the lines of: Global cooperation for better pandemic preparedness is in Australia’s interests, and so of course we support the WHO having a greater role and of course we intend to comply. Are Australians complacent and/or stupid enough to swallow this rhetoric?

The UK’s Health Minister Andrew Stephenson said during a parliamentary debate on 18 December 2023 that this is a red-line issue for the UK government. He even went so far as to give a “categorical assurance”:

I can give a categorical reassurance to my right hon. Friend that that is a red line for the UK Government. We would never allow the World Health Organisation to impose a lockdown in the UK. That is a clear red line for us. I cannot think of any Minister who would agree to such a request.

I can confidently say to my colleagues—as someone who campaigned for Brexit and who has helped to deliver Brexit in this place—that I am passionate about this country’s sovereignty. I believe that the Government’s position needs to be crystal clear and it is one that I endorse. We support the member state-led process of agreeing targeted amendments to the IHR and the new pandemic accord for the sake of global health preparedness, but we will not agree in any circumstances to provisions that would cede sovereignty to the WHO. That includes the ability to make decisions on national public health measures, whether lockdowns, which we just mentioned, or vaccine programmes.

(emphasis added)

It might be nice if the Australian Health Minister or Prime Minister could reassure us that it is also a redline issue for the Australian government, and if they could do this now, rather than making us wait with bated breath for the National Interest Analysis to be tabled mid 2024.

Australians need to understand that parliament’s role in determining whether we become legally obligated to follow the WHO’s “recommendations” will be very minimal. At best JSCOT might be a catalyst for the government to feel some heat on this issue. To the extent that parliamentarians do not yet understand yet the truth of the situation, it will be JSCOT’s job to wake them up, and they will have to work fast. Once the amendments are tabled sometime in mid 2024, there will be less than a year for us to reject them. In addition to the short time frame, the amendments are very complex, and JSCOT will be dealing with the proposed pandemic treaty at the same time.

If JSCOT does its job properly it will strongly recommend the government at least rejects the proposed amendments to articles 1, 13A, 42 and 43, which render the WHO’s “recommendations” binding, or even better, reject the whole shooting match.

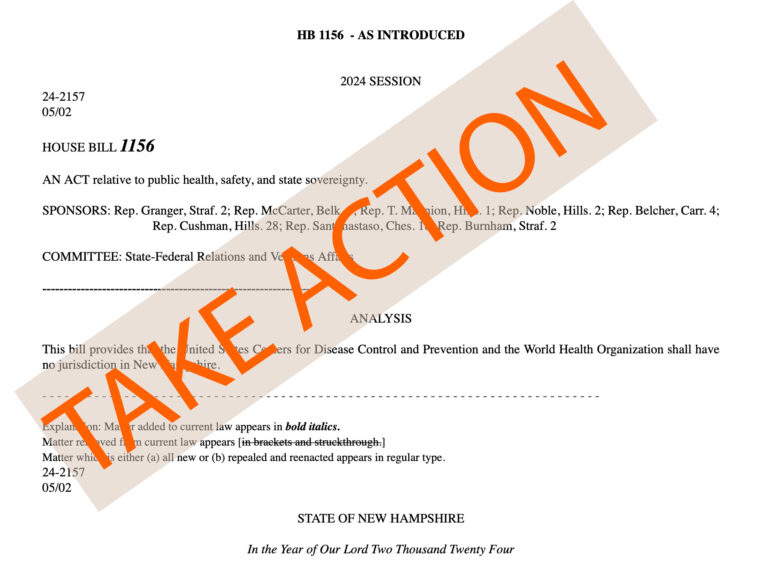

If the government fails to respond, or responds by rejecting that recommendation, we need to either elect a new Commonwealth government before March 2025 (the deadline for rejecting the amendments) and/or encourage our State and Territory governments to pass legislation nullifying the Commonwealth’s acceptance of the amendments. Health is after all a matter for the States and Territories under the Australian constitution. Many US States are well down this route. If this seems extreme, that’s because it is, and for good reason: the very ability of our nation to make our own decisions is at stake.

[1] Capling A, Nossal KR. Parliament and the Democratization of Foreign Policy: The Case of Australia’s Joint Standing Committee on Treaties. Canadian Journal of Political Science. 2003;36(4):835-855. doi:10.1017/S0008423903778883