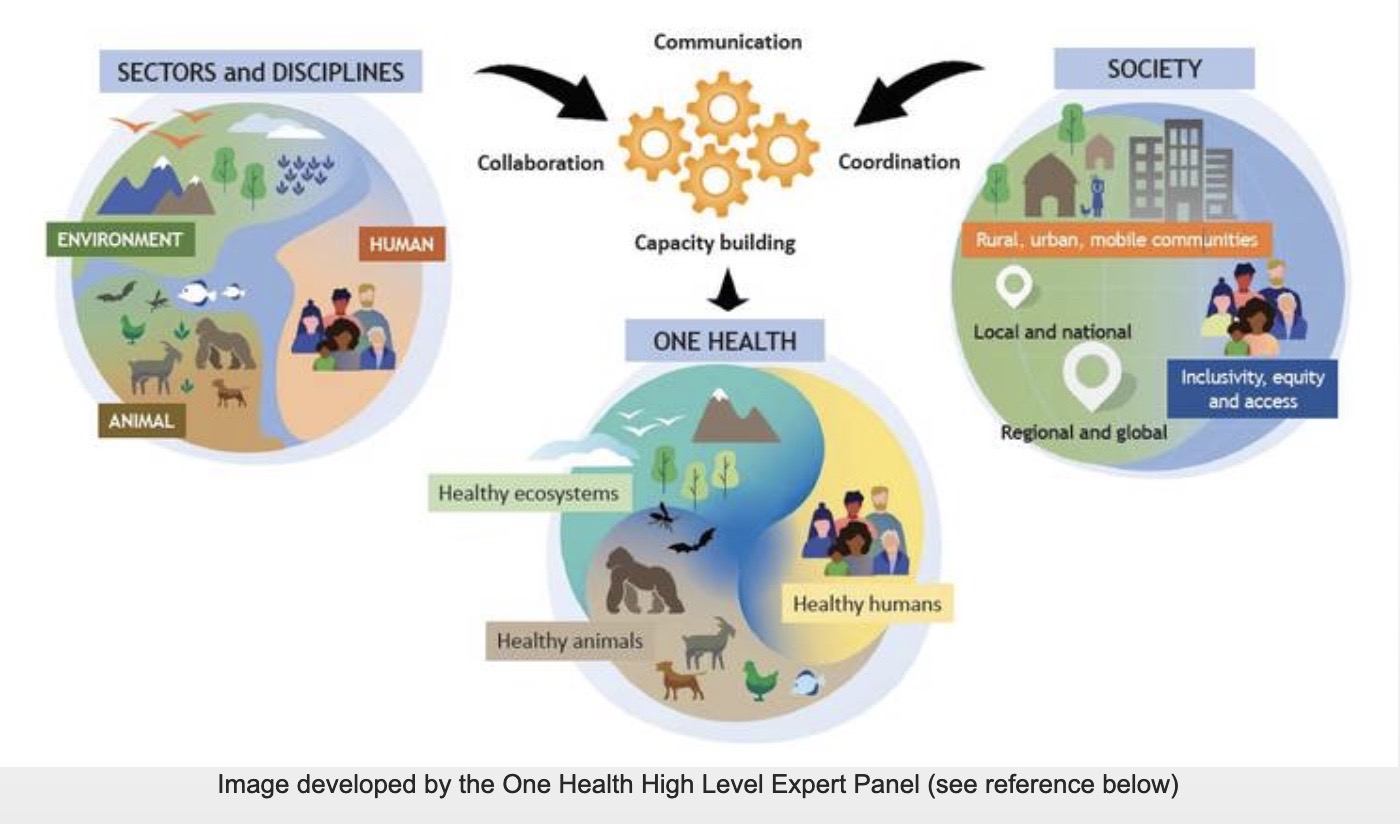

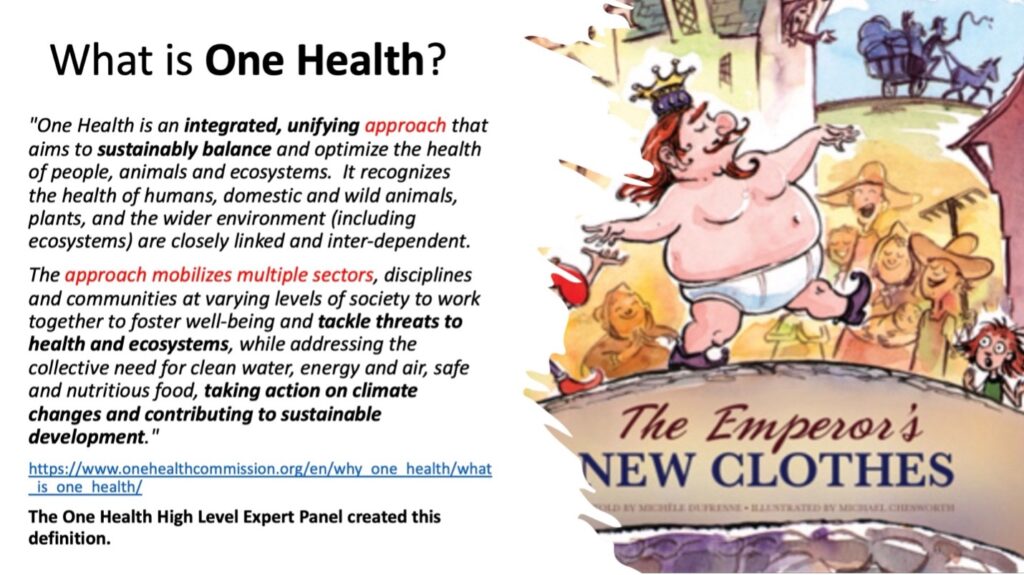

“One Health” was conceived 20 years ago as the idea that human health and animal health are intertwined, since some diseases are transmitted from animals to humans. These diseases would perhaps be better managed with specialists in animal and human health working together.

Subsequently the WHO, the US government and many other governments and organizations decided that One Health should include all plants and ecosystems. The “One Health approach” would involve specialists in every area working together to solve health problems. However, sending a plant pathologist or ecologist to work on human health issues never made sense.

But in just a few years, well-funded One Health offices sprang up throughout governments, public health departments and universities around the world. Meanwhile, the definition of One Health continued to expand. The CDC’s One Health office included police and legislators when it described the One Health approach:

Successful public health interventions require the cooperation of human, animal, and environmental health partners. Professionals in human health (doctors, nurses, public health practitioners, epidemiologists), animal health (veterinarians, paraprofessionals, agricultural workers), environment (ecologists, wildlife experts), and other areas of expertise need to communicate, collaborate on, and coordinate activities.

Other relevant players in a One Health approach could include law enforcement, policymakers, agriculture, communities, and even pet owners [emphasis added]. No one person, organization, or sector can address issues at the animal-human-environment interface alone.

https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/index.html

Recently four international organizations joined together to advance One Health in a collaboration termed “The Quadripartite.” It includes the World Health Organization, the Food and Agricultural Organization, the United Nations Environmental Program and the World Organization for Animal Health.

In the US, “One Health” was embedded in federal agencies as its remit grew. The CDC now claims,

“Even the fields of chronic disease, mental health, injury, occupational health, and noncommunicable diseases can benefit from a One Health approach involving collaboration across disciplines and sectors.”

But the various One Health commissions and expert panels have had trouble demonstrating that a One Health approach to problem-solving is actually useful. Where is the evidence?

The Lancet‘s One Health Commission produced a number of articles about One Health, and one described a search to verify the benefits of the One Health approach. Titled “Advancing One human-animal-environment Health for global health security: what does the evidence say?”, the authors found:

One Health approaches show quantitative incremental benefits.… Further research is needed to show financial savings, co-benefits, and trade-offs associated with One Health operationalization and systematic evidence reviews are required to assess the effectiveness of One Health approaches to address threats to global health security.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(22)01595-1/fulltext

In other words, even the Lancet One Health Commission could not find proof that the One Health approach saves money or improves health security.

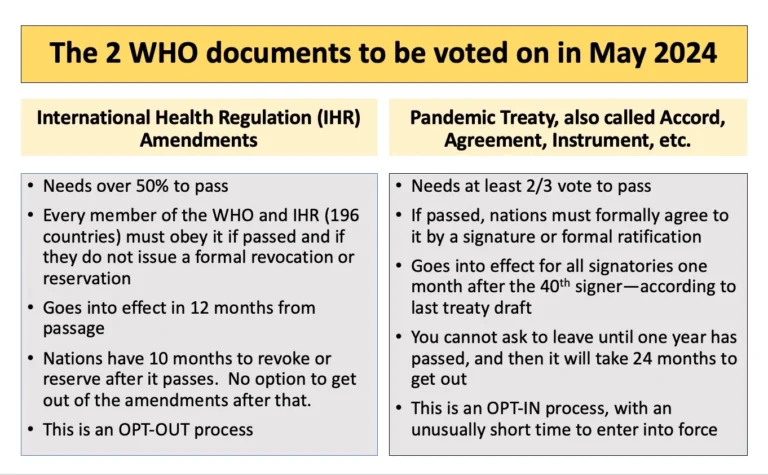

But one notable thing that One Health has accomplished is to put humans, animals, plants and ecosystems under the jurisdiction of the WHO director-general. This is because the ‘One Health approach’ must be used, as required by US law [1] as part of pandemic preparedness, and the One Health approach is a requirement of the WHO’s proposed pandemic treaty.

“It’s clear that a One Health approach must be central to our shared work to strengthen the world’s defenses against epidemics and pandemics such as COVID-19. That’s why One Health is one of the guiding principles of the new international agreement for pandemic prevention, preparedness and response, which our Member States are now negotiating,” said WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. [2]

The inclusion of the “One Health Approach” in the WHO’s proposed pandemic treaty gives the WHO director-general the ability to issue orders to all nations regarding humans, animals, plants and ecosystems when a public health emergency is declared. [3] And public health emergencies can be broadly defined. Top medical journals have claimed that global warming is the greatest threat to public health. [4] [5]

One Health is problematic because it is the mechanism by which many other issues can be placed under the umbrella of public health, and then managed solely by the WHO whenever it declares an emergency.

[1] The 2023 National Defense Authorization Act 2023. pages 950-967.

Subtitle D—International Pandemic Preparedness. SEC. 5559. SHORT TITLE. This subtitle may be cited as the ‘‘Global Health Security and International Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response Act of 2022.

https://www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ263/PLAW-117publ263.pdf

[2] https://www.who.int/news/item/17-10-2022-one-health-joint-plan-of-action-launched-to-address-health-threats-to-humans–animals–plants-and-environment

[3] Under the current draft of the WHO IHR, the WHO director-general can declare a Public Health Emergency of International Concern based on no specific evidence, or based on the potential for a pandemic. Article 12, IHR Draft February 6th 2023

[4] https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMe2113200

[5] https://www.npr.org/2021/09/07/1034670549/climate-change-is-the-greatest-threat-to-public-health-top-medical-journals-warn