Updated October 30 2023.

July 14, 2023 Summary:

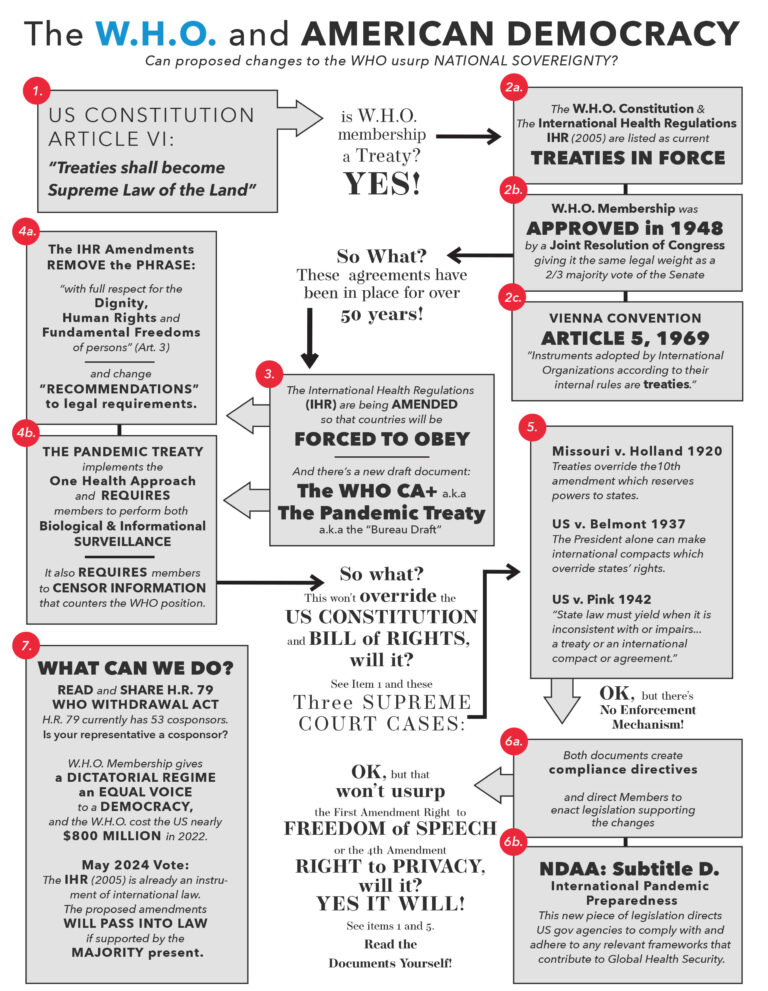

The World Health Organization members adopted a set of principles termed the International Health Regulations (IHR) in 1969 [1] to guide the conduct of nations during health emergencies affecting more than one country, especially malaria and smallpox. The IHR was amended in 2005 [2]. The WHO states:

The International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR) provide an overarching legal framework that defines countries’ rights and obligations in handling public health events and emergencies that have the potential to cross borders.

While the current IHRs have been considered recommendations and not orders, the members of the World Health Assembly (the WHO member states) decided to amend the existing IHR in May 2022. [3] Currently only drafts, and not the final IHR proposal, are available. The drafts have revealed that the newly proposed amendments seek to be binding on all nations. In other words, unless a country formally rejects the new amendments, it will be required to obey them whenever the WHO Director-General declares a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

A total of 307 amendments were proposed during 2022 by 94 member nations. The proposed amendments were first made publicly available in mid-December, 2022 [4] and were republished on February 6, 2023. [5]

The proposed Amendments would allow the WHO Director-General to assume the authority to direct healthcare around the world whenever he declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. He has already declared 3 (for Ebola, COVID-19 and monkeypox) during his six years in office.

Among the new provisions in the proposed IHR amendments are the following:

- Vaccine passports

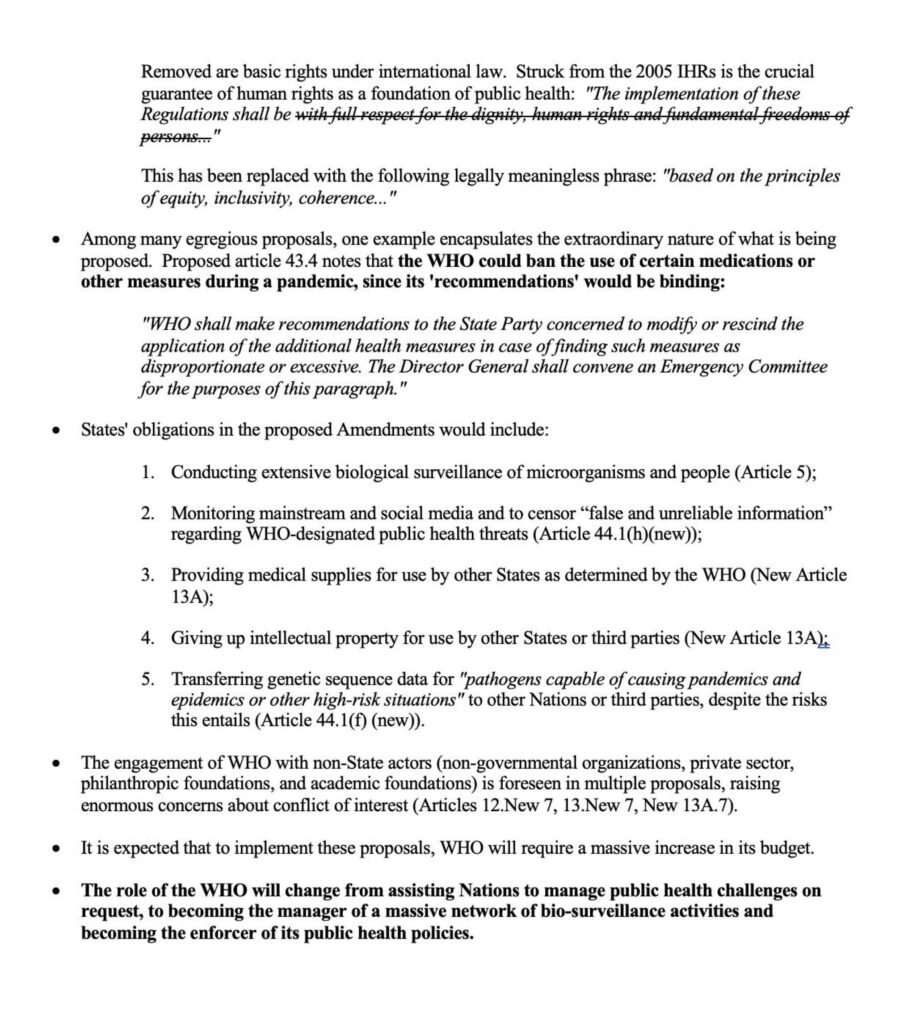

- The guarantee of human rights has been struck out, removing the words “with full respect for the dignity, human rights and fundamental freedoms of persons,” which are present in the current version of the IHRs

- The potential to enforce certain medical treatments and ban others

- A requirement for biological surveillance (such as PCR tests) to be performed on humans and animals in search of pandemic pathogens

- The requirement to monitor social media and allow only the WHO’s narrative on public health to be transmitted

- The ability to commandeer medical supplies within one country for use by another

- The requirement to share genetic sequences of pathogens, even though this could result in proliferation of biological weapons, which is banned by existing treaties such as Resolution 1540 (2004) of the UN Security Council and the Biological Weapons Convention (1972)

Furthermore, the current draft IHRs include no specific criteria for the Director-General of WHO to declare a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). A declaration could even be made without the consent of the involved nations. And there are no provisions that make WHO officials accountable for their actions. Equally concerning, a PHEIC declaration can be issued for merely the potential for a public health emergency, and the emergency powers can be extended beyond the end of the emergency.

The proposed IHR amendments raise the possibility of a global health dictatorship, called at the whim of the WHO leadership or the whim of the WHO’s major funders. Why the WHO should take on these powers, when its performance during COVID-19 was far from stellar, is an important question.

The proposed amendments will be considered for adoption at the 77th World Health Assembly during the last week of May, 2024.

Footnotes

[1] https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85816/Official_record176_eng.pdf

[2] https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241580496

[3] https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA75/A75%289%29-en.pdf

[4] https://apps.who.int/gb/wgihr/pdf_files/wgihr2/A_WGIHR2_7-en.pdf

[5] https://apps.who.int/gb/wgihr/pdf_files/wgihr2/A_WGIHR2_6-en.pdf