This article is a repost with the kind permission from CHD Africa

I attended a World Health Organisation press conference about responding to sexual abuse and exploitation by staff members in countries they are deployed. The conference was against the horrific backdrop of sex-for-work schemes and the exploitation of women during 2018-2020 Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The WHO deployed more than 1500 staff members to assist in the outbreak.

Background

According to The New Humanitarian:

“Some women said they had worked for WHO during the Ebola response as cooks, cleaners, and community outreach workers, earning $50 to $100 a month – more than twice the average wage. Job opportunities have been scarce for women in eastern DR Congo, which has been embroiled in one of the longest running humanitarian crises in history.

Many women recounted being plied with drinks, ambushed in offices and hospitals, and preyed upon at job recruitment centres. Some said they were locked in rooms by men who promised jobs or threatened to fire them if they refused to have sex. Many said they were impregnated or had contracted venereal diseases.”

Who are the perpetrators?

According to The New Humanitarian:

It took more than a year after the scandal broke for investigators to reach many of the victims. It took another year for many to be given updates on their cases or to learn what type of assistance they may receive.

Of the 83 cases noted by the independent commission, 23 were found to be associated with WHO personnel, Gamhewage said, adding that the remainder of allegations were against other UN agencies and humanitarian agencies.

The majority of allegations in the scandal involved WHO. But workers from UNICEF, Oxfam, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), World Vision, ALIMA, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), International Medical Corps (IMC), and the International Rescue Committee (IRC) were also implicated.

One of the nine rapes cited by the WHO’s independent commission was that of a 13-year-old. In 2022, Gamhewage, who was appointed Director, Prevention of and Response to sexual misconduct said “13 victims are pursuing legal actions, but she had no other information on what the cases involved or which organisation the alleged perpetrators worked for.”

Ongoing sexual exploitation

According to The New Humanitarian:

“What happened to you should never happen to anyone,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO’s director-general, said of the victims at a news conference in 2021, after the publication of the independent commission’s report. He apologised to the women and called it “a dark day for WHO”.

However, similar abuses had been reported earlier, during the WHO-led response to the West Africa Ebola outbreak between 2014 and 2016. Several more UN and aid sector sexual abuse scandals made headlines in the years that followed.

Despite the earlier scandals, the independent commission noted in its report that WHO was “completely unprepared to deal with the risks/incidents of sexual exploitation and abuse” during the DR Congo Ebola outbreak.

What happened and why the cover up?

According to an AP investigation:

- When Shekinah was working as a nurse’s aide in north-eastern Congo in January 2019, she said, she was offered a job from a World Health Organization doctor at double her salary — in exchange for sex.

- “Given the financial difficulties of my family … I accepted,” said Shekinah, 25, who asked that only her first name be used for fear of repercussions. She said the Canadian doctor, Boubacar Diallo, who often bragged about his connections to WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, made the same proposition to several of her friends.

- When a staffer and three Ebola experts working in Congo informed WHO management about sex abuse concerns regarding Diallo, they were told not to take the matter further, The Associated Press has found.

- WHO has been facing widespread public allegations of systemic abuse of women by unnamed staffers, to which Tedros declared outrage and emergencies director Dr. Michael Ryan said, “We have no more information than you have.” However, an AP investigation has now found that despite its public denial of knowledge, senior WHO management wasn’t only informed of alleged sexual misconduct in 2019 but was asked how to handle it

- Eight top officials privately acknowledged WHO failed to effectively tackle sex abuse during the Ebola outbreak, emails, recordings of internal meetings, legal documents and interviews with dozens of aid workers and WHO staffers show. WHO declined to comment on any specific sex abuse allegations or how they were managed and said it had taken steps to address the problem.

- “We are aware that more work is needed to achieve our vision of emergency operations that serve the vulnerable while protecting them from all forms of abuse,” WHO spokeswoman Marcia Poole said in an email.

- WHO emergencies chief Dr. Michael Ryan acknowledged in internal meetings that sexual abuse problems during the agency’s outbreak responses were unlikely to be exceptional. “You can’t just pin this and say you have one field operation that went badly wrong,” he said. “This is in some sense the tip of an iceberg.”

- On Oct. 15, Tedros appointed an independent panel to investigate sex abuse during the Ebola outbreak in Congo; no findings are expected until the end of August. At a town hall meeting in November, Ryan acknowledged sex abuse issues had been “neglected” for years.

High level cover up

According to Health Policy Watch:

An inquiry directed by the commission interviewed some 3063 women witnesses, aged 13-43 years, along with 12 men – all alleged to have been exploited and abused by the Ebola response teams that included about a dozen other UN organisations and NGOs, coordinated by WHO with the DRC government.

But Tedros, who visited DRC 14 times during the Ebola outbreak, also said that he had never heard word of the widespread abuse when he was in DRC on the ground. “The issue was not raised to me, probably I should have asked questions. As for the next steps. What we’re doing is we have to ask questions,” he said.

Speculation about high-level WHO cover-up has revolved mostly around the WHO Emergencies Official, Michael Yao, who was reported by the Associated Press to have received a series of confidential emails naming some of the alleged abusers, including Dr Boubacar Diallo – but did not take action against the alleged perpetrators.

Diallo described by colleagues as having connections to WHO’s senior leadership, reportedly denied the wrong-doing. In one WHO photo, Tedros, Yao and Diallo are pictured smiling together during one of Tedros’ trips to Congo during the Ebola outbreak.

Neither man was mentioned by name at Tuesday’s media briefing. But the panel’s written report does refer to the “case of M. Boubacar Diallo, stating that “Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus, during his interview with the investigators, acknowledged that he had instructed Mr David Webb, who had come to inform him in January 2021 of incidents involving Mr Diallo, to defer any internal investigation until the publication of the conclusions of the Independent Commission and to transmit to the latter all the information at his disposal.

The AP published evidence showing that Dr. Michel Yao, a senior WHO official overseeing the Congo outbreak response was informed in writing of multiple sex abuse allegations. Yao was later promoted and recently headed WHO’s response to the Ebola outbreak in Guinea, which ended in June 2020.

WHO’s response to Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Dr Boubacar Diallo, WHO Director-General, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and WHO Emergency Response Team leader, Dr Michael Yao. Title of WHO staff and officials reflects their respective position at the time the photo was taken.

Reparations and empty promises

According to Health Policy Watch:

After suffering abuse during the 2018-2020 Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, many women who were promised support in 2021 received one-time payments of $250 – the rough equivalent of two days’ worth of per diems for UN staff.

- Support and justice for Ebola sex abuse victims

- Assistance given to 104 women so far; 11 refuse

- Women have been given one-time payments of $250

- Counselling, medical support, and toiletry bundles offered

- Half the victims have yet to be reached for legal assistance

- Dozens of additional women report new abuse claims

- No UN personnel have been referred for potential prosecution

The New Humanitarian and the Thomson Reuters Foundation first uncovered the scandal in 2020, publishing a second investigation in 2021. The reporting prompted WHO to appoint an independent commission, which confirmed in 2021 that WHO workers had lured women into sex-for-work schemes. A number of other UN agencies and aid organisations were also named by women.

Although the independent commission recommended in its report that “reparations” be made to the victims, WHO said UN rules prohibit such payments. Investigations into the abuse are still ongoing. WHO’s global budget for the prevention of sexual exploitation, abuse, and harassment is $50 million.

Despite recommendations from the independent commission, WHO has said repeatedly that UN rules prohibit paying reparations. The UN itself, however, has called for reparations to be made in cases of human rights violations and conflict-related sexual violence.

Some organisations, like the Catholic Church, have sold off assets to pay reparations to victims of sexual abuse. Other groups found liable for abuses have been successfully sued for compensation and damages.

Temporary contract workers – as many women abused in the Ebola sexual abuse scandal were – lack access to the full extent of UN justice mechanisms. UN staff, by contrast, have been awarded settlements of more than $100,000.

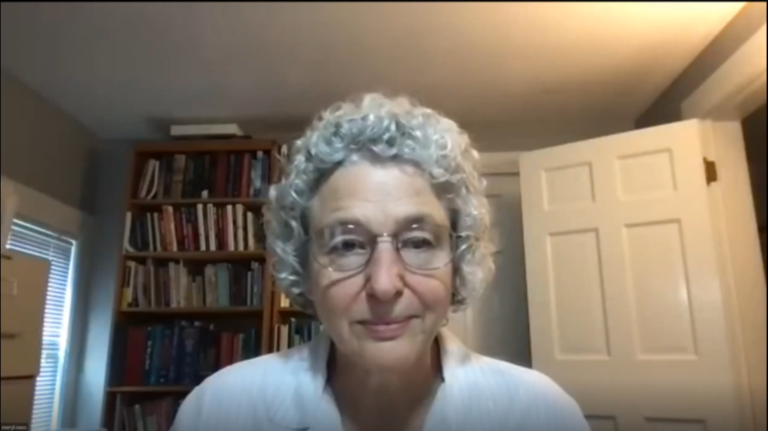

The SEAP conference I attended

Speaking at the oddly short press conference I attended were Dr Gaya Gamhewage, Director, Prevention of and Response to sexual misconduct, WHO; Mr Hervé Gogo, Reviewer, implementation of the recommendations of the Independent Commission; Ms Lisa Mc Clennon, Director, Internal Oversight Services, WHO; and Ms Sigrid Kranawetter, Pritncipal Legal Officer, WHO.

Dr Gamhewage stated that 10% of 78 targets set by WHO have been achieved. She spoke about the WHO supporting 115 survivors of WHO staff inflicted sex abuse and exploitation in the DRC. She referred to a strong policy2 framework, and that the WHO has new policies and a code of ethics to address retaliation against survivors. According to Dr Gamhewage, the WHO intends to support survivors of sex crimes, exploitation and harassment by staff in other United Nations agencies. She mentioned that UN fieldworkers would assist in the WHO programme. While there were 48 allegations against personnel, 6 were substantiated and 7 staff were dismissed. In the DRC, she said, the WHO gave information on 16 perpetrators to the government. Thirteen survivors were receiving WHO legal assistance.

Mr Gogo then presented his review on the WHO’s progress since the independent commission’s 2021 report3 on WHO staff inflicted abuse and exploitation. He talked about four focus areas: accountability, strengthening the programme, survivor assistance and government co-operation. He mentioned conflicts of interest in the outsourcing of investigations. He also stated that investigations were taking too long to complete. Part of the challenge was identifying the perpetrators. The budget allocated to the sexual abuse and exploitation programme was 50 million USD. He confirmed that further programme capacity building and victim support is needed, along with victim reparation mechanisms.

Mr Gogo reminded that the WHO was not the only agency accused of abuse, exploitation and harassment. DRC women also noted that men came from UNICEF, Oxfam, Médecins Sans Frontières, World Vision, ALIMA, and the International Organization for Migration.

Three media questions were answered, one of which was whether WHO director-general Adhanom Tedros Ghebreyesus knew anything about the abuse and exploitation. Mr Gogo stated that, according to his investigations, Tedros did not know. Unsurprisingly, my question on WHO conflicts of interest related to investigations was not addressed.

According to Dr Gamhewage, Dr Tedros did not attend this press conference as he was in other meetings. She indicated that the WHO intends to host more briefings in future. The ongoing human rights crisis in the DRC is reflective of the adage ‘justice delayed is justice denied’.

The dangers of WHO announced PHEICS

According to the New Humanitarian, the WHO also announced it was allocating an initial $7.6 million to strengthen its capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to sexual abuse allegations in 10 countries with the highest risk profile. Those included: Afghanistan, Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Venezuela, and Yemen.

In my analysis, the announcements of public health emergencies of international concern (PHEIC) by the WHO, as amplified in International Health Regulations and the proposed new pandemic treaty – and the power grab by the United Nations – are a conduit to sexual exploitation, socio-economic deprivation, and human trafficking. Member states have the right to reconsider their participation in the WHO. In Africa, collaboration – for example through community, national, and other alliances – can be more conducive to health and well-being.

Sources include:

- https://apnews.com/article/united-nations-europe-ebola-virus-entertainment-coronavirus-pandemic-d14715ba3653753d7c1f122f8aea79de

- https://apnews.com/article/crime-democratic-republic-of-the-congo-united-nations-niger-world-health-organization-b90517846748b161983350ec0c5296ca

- https://apnews.com/article/business-health-united-nations-world-health-organization-ebola-virus-36ceb41d266190d149a74e400332e1ed