The United Nations (UN) produced a series of 11 ‘Policy Briefs’ [1] in the spring of 2023 under the theme “Our Common Agenda.” These provide specific ideas about how the UN wants to achieve its Sustainable Development Goals, while the policy briefs still leave a lot unsaid.

One of the briefs proposes that the UN assume international management of certain ‘global shocks.’

I have taken some of the language straight from this UN policy brief [2] on page 12:

When the world faces a complex global shock, we must ensure that all parts of the multilateral system are accountable for contributing to a collective response. No single agency exists to gather stakeholders in the event of complex global shocks. The United Nations is the only organization that can fulfil this role.

I propose that the General Assembly provide the Secretary-General and the United Nations system with a standing authority to convene and operationalize automatically an Emergency Platform in the event of a future complex global shock of sufficient scale, severity and reach.

[emphasis added by author]

The UN claims that the ‘only’ way we can adequately respond to global emergencies (which the UN terms ‘complex global shocks’) is through the UN, by galvanizing global action. However, this is obviously not the only way to approach emergencies affecting multiple countries, since we have managed so far without the UN’s emergency platform.

Another concern is using the terms “standing authority,” and “operationalize automatically the emergency platform.” ‘Standing authority’ means that the UN Secretary-General has already been given the authority by the UN members and can then use it at will. ‘Operationalize automatically’ suggests no further authority would be needed for the UN to use its new emergency powers. This opens the door to the UN Secretary-General declaring an emergency or shock using his standing authority and then the UN would automatically take charge, directing countries what they must and must not do.

The problem is that disaster management is always local. Local resources deal with the problem immediately when it occurs. State, national or United Nations troops, supplies, and logistics take days or weeks to organize and arrive. Central authorities generally swoop in after the emergency has already been managed. We certainly don’t need central governing authorities telling the local authorities what they can and cannot do, when in fact the local authorities are the only ones there at the scene of the emergency.

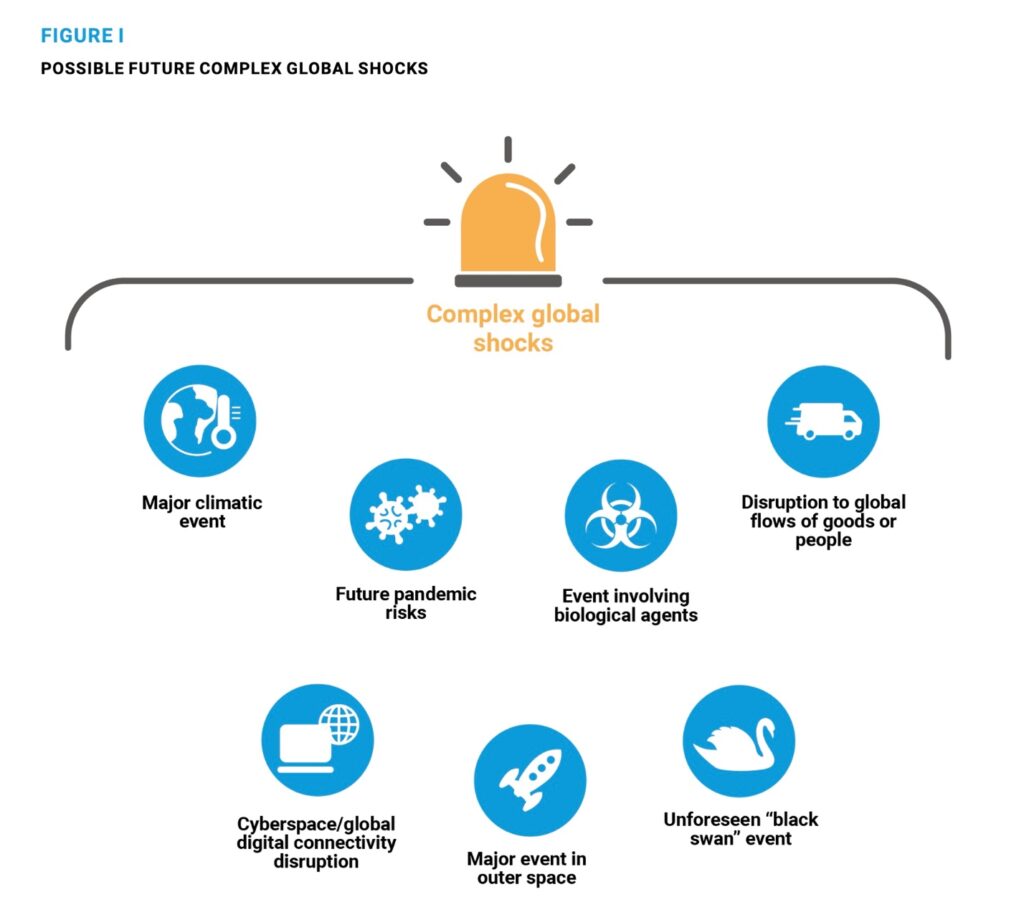

What emergencies does the UN think we might need them to manage? The policy brief [3] offers this list of global shocks on page 6.

An emergency could be declared over climate! Or a disruption to the internet or grid. An event in outer space (which may not even be noticed on earth) might lead to the UN asserting itself to manage things.

The UN appears to be jockeying with the WHO to manage pandemics and bioterrorism, even though the WHO is rushing through a pandemic treaty and new International Health Regulation amendments that do the very same thing, right now.

Worst of all, the UN has said that ‘black swan events’ might trigger the UN to take over. Black swan events [4] are incidents that are unusual and unexpected. In other words, the UN could declare any kind of crisis it liked a ‘black swan event,’ leading the UN to jump in and manage whatever it is.

But the problem is that the UN has no expertise or staff with experience managing all possible crises. Furthermore, UN staff are not elected by the world’s population and are not accountable to them. Turning over the authority for managing ‘global shocks’ to a political agency that can choose the shocks it wants to manage, and how it wants to manage them, seems foolhardy at best.

Footnotes

[1] https://www.un.org/en/common-agenda/policy-briefs

[2], [3] https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/our-common-agenda-policy-brief-emergency-platform-en.pdf