a) impenetrable last-minute legalese, b) a history of making reservations that enable the US to dodge compliance, and c) scuttling carefully negotiated agreements

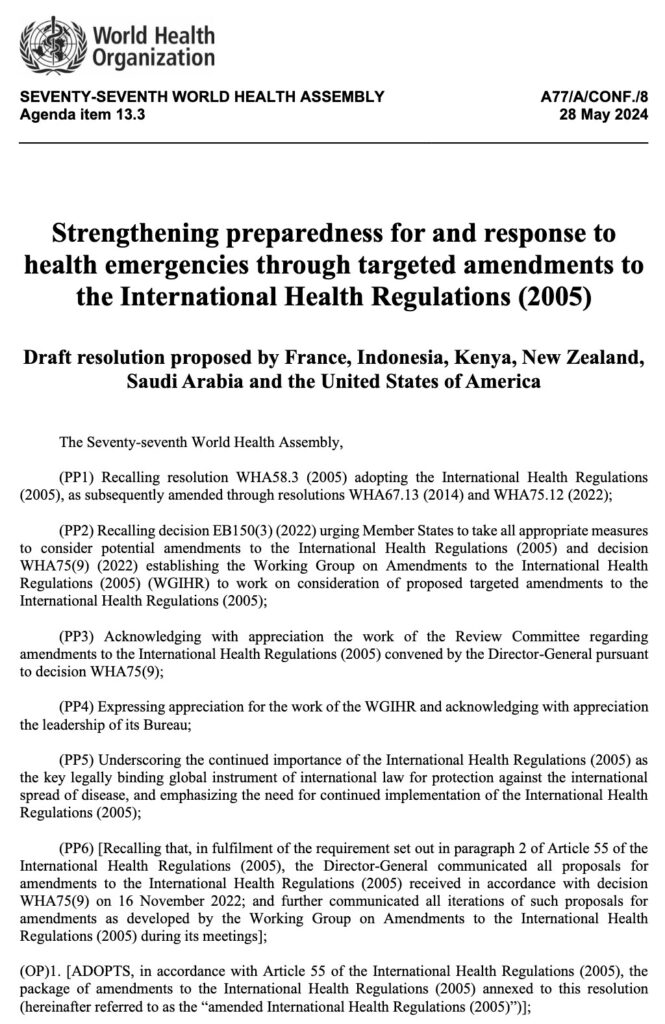

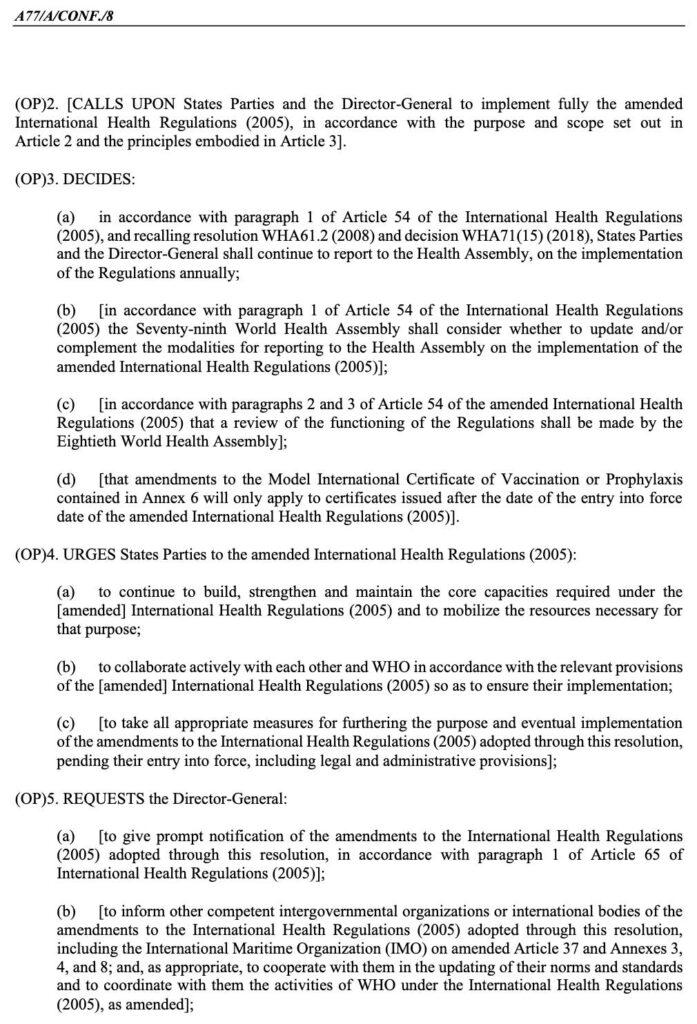

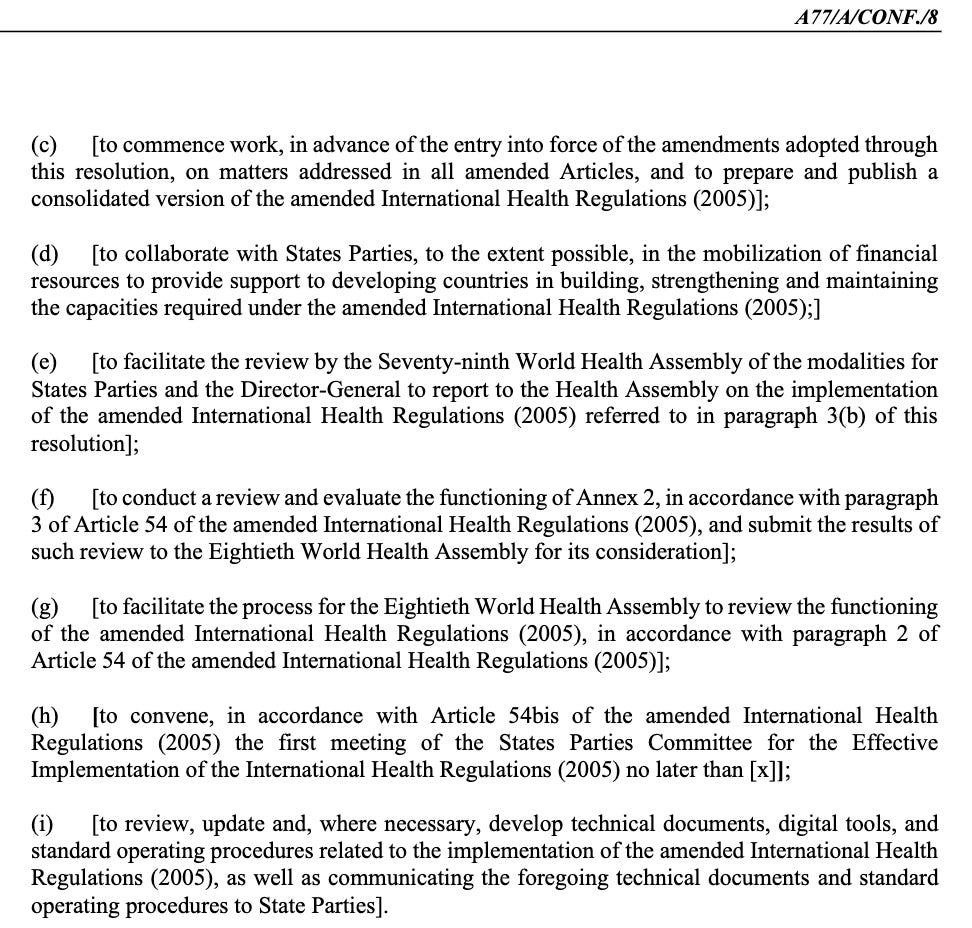

Example #1. Here is a resolution the US and a handful of its hangers-on proposed for the WHA to approve today. It is so full of references to other documents (by number) that it is impossible to tell what it is actually asking the members to commit to. And, since it was only proposed today (but no doubt most of it was prepared earlier) the member nations have little time to carefully review it in light of the packed agenda of the week, with meetings scheduled during 12 hours a day.

No wonder the US delegation to the 2022 World Health Assembly was composed of 65 people. They were there in part to produce abstruse documents like this, for all contingencies.

No wonder small nations cannot keep up. That is the point. This document was written to be impenetrable. And the schedule was designed to wear everyone down.

[Don’t miss Example #2, which is even more damning.]

I think the USG lawyers were too clever by half when they wrote the resolution above. Everyone reading it can see it was intended to obfuscate rather than illuminate. I doubt this document will make many friends, and I doubt it will get very far.

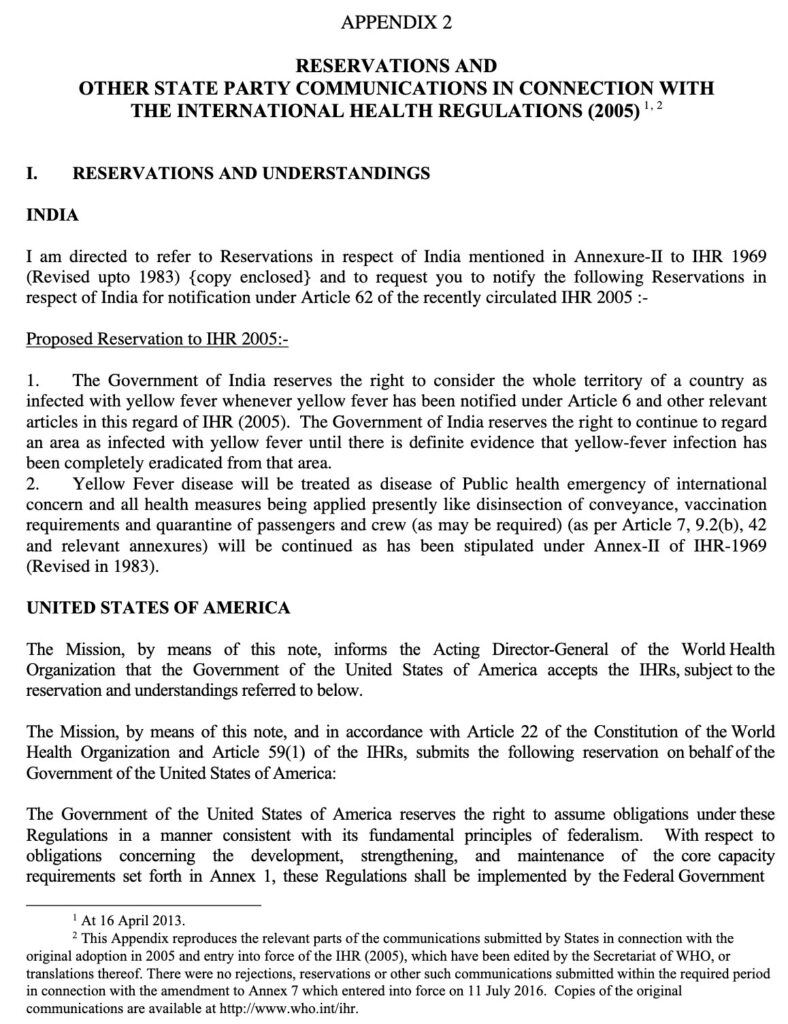

Example #2. Now let us observe how the US government weaves the noose around everyone else’s head, but slips out itself at the last minute.

The International Health Regulations (IHR, 2005) are a treaty that the US is a party to. But the US removed itself from meeting the obligations contained in the treaty through issuing the following reservations, found on pages 60-61 of the IHR or on the State Department website. We “accept” the IHR but only “subject” to the following:

Dodge #1: The US government hid behind the skirts of its States, saying that according to the US Constitution the US obligations to the IHR might come under state and not federal jurisdiction. And in that case the USG could not promise to comply. [Well, we sure got them on that one this month! Two can play that game.]

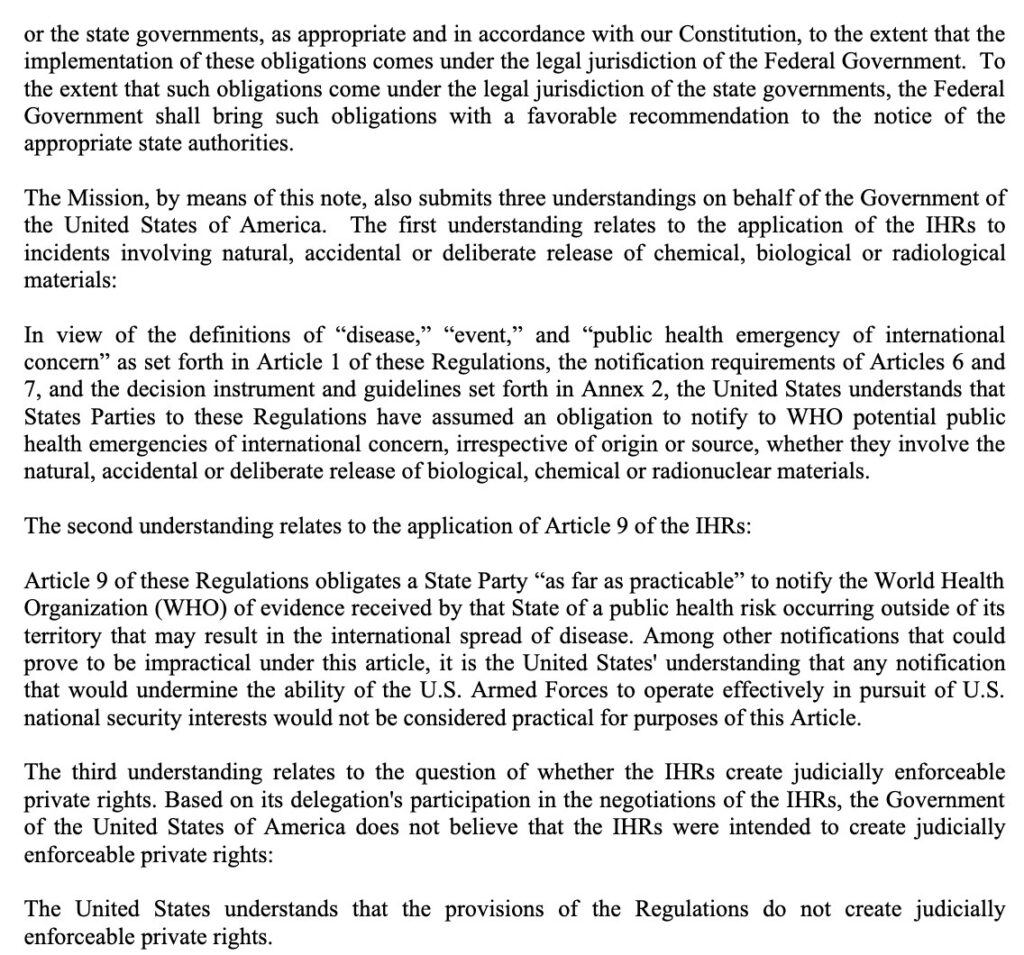

Dodge #2: While the US insists China failed to meet its obligation to notify the world of COVID in a timely manner, the USG wanted to be able to dodge that same obligation in the IHR to report infectious outbreaks quickly. So if reporting might affect the US military and national security, the US refused to accept the obligation to report.

Dodge #3: Here is the language:

The third understanding relates to the question of whether the IHRs create judicially enforceable private rights. Based on its delegation’s participation in the negotiations of the IHRs, the Government of the United States of America does not believe that the IHRs were intended to create judicially enforceable private rights:

The United States understands that the provisions of the Regulations do not create judicially enforceable private rights.

If I understand the third dodge correctly, the USG is claiming that just because the US signed the IHR treaty, this did not convey any rights to other signatories. And therefore the US is not subject to litigation if it does not comply with treaty provisions as interpreted by other signatories.

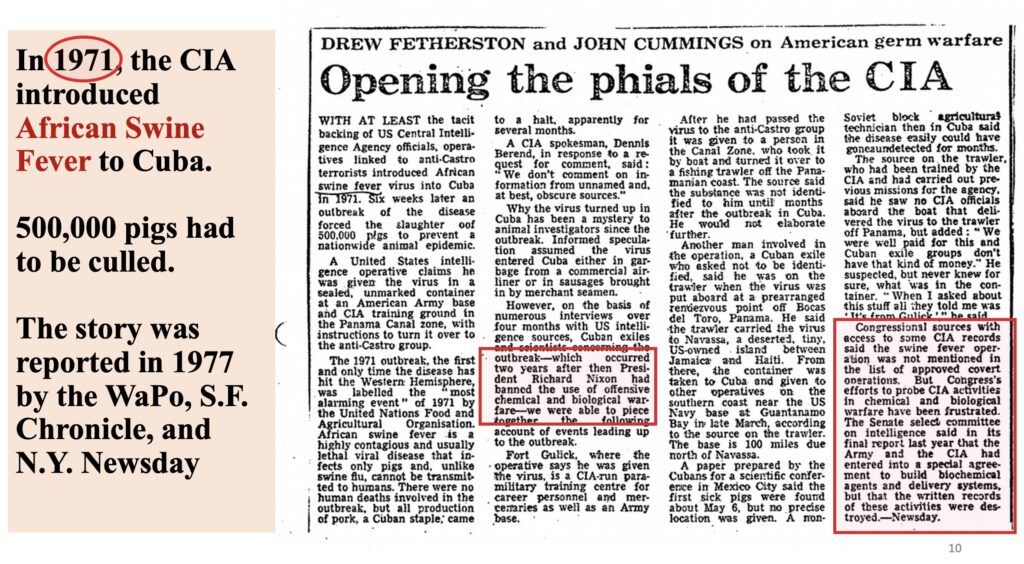

Final Dodge: Sometimes the US goes all the way to the end with difficult treaty negotiations, then refuses to sign at the last minute. This is what happened when the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) Review Conference thought it had finally achieved consensus on provisions for inspections, and punishments for noncompliance with the BWC treaty in 2001. When everything was set, the US abruptly said “NYET” and the amendments to the treaty were scuttled.

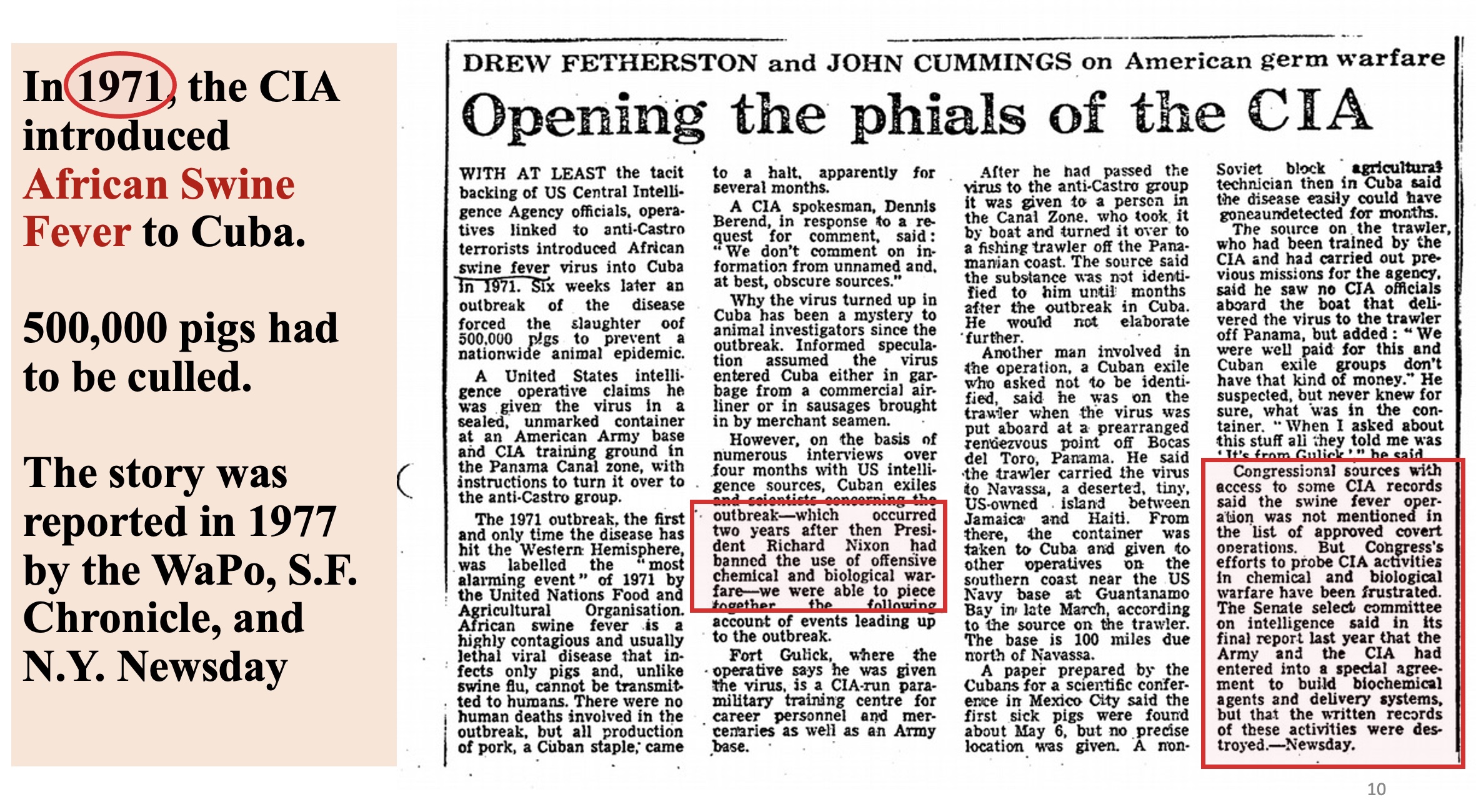

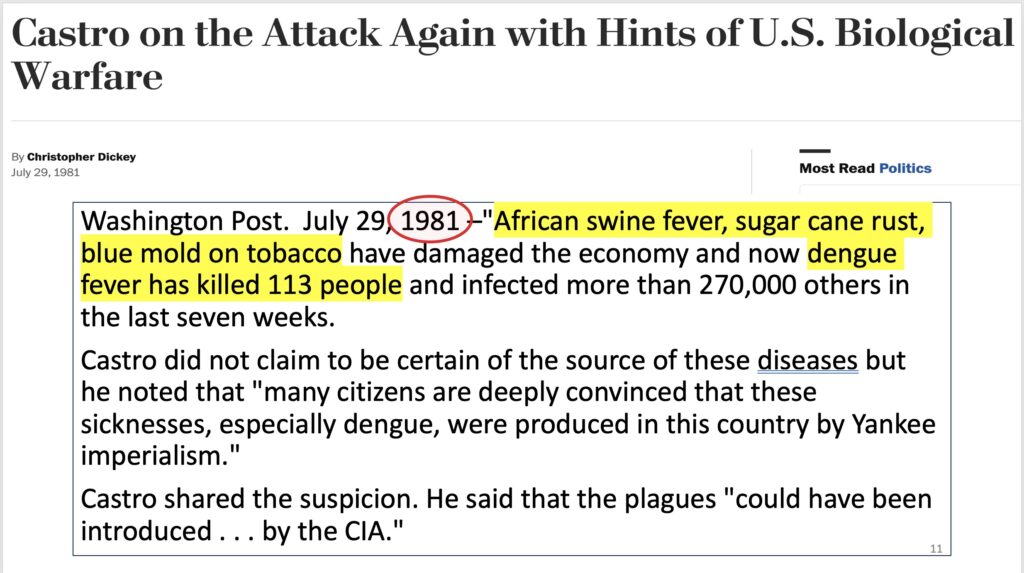

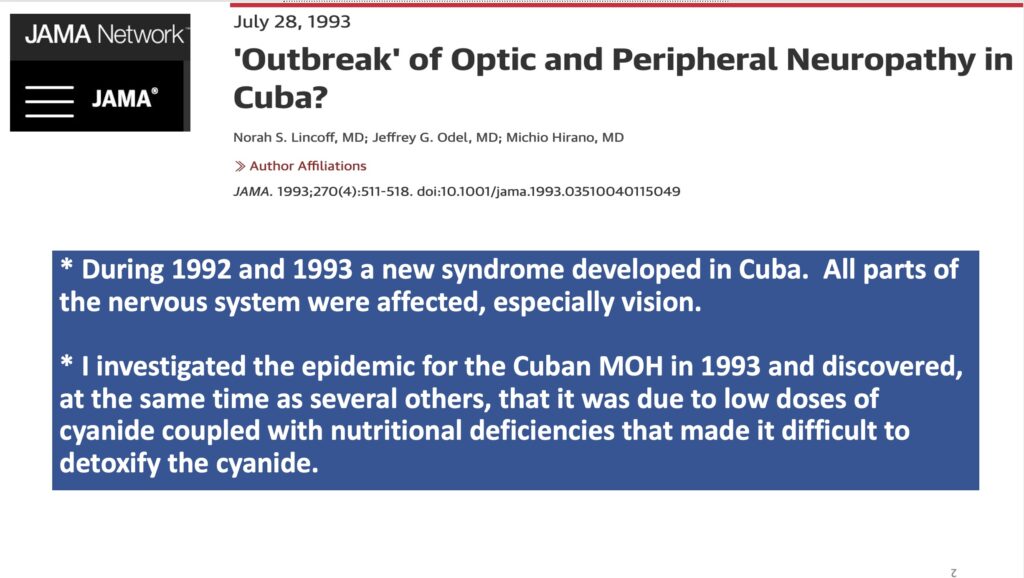

I did not understand why the US did this at the time, but subsequently realized that Cuba alleged that the US used biological weapons on Cuba after the US had become a party to the Biological Weapons Convention. (Here is my recent mention of several examples.)

If true, and the evidence is very strong that it is, the US would not have wanted to be subject to inspections and investigations of those allegations.

The bottom line is that perhaps every country should be as careful to protect itself from potentially invasive or harmful provisions in treaties that it signs, as the US historically has been. This would level the playing field and make the treaty process more equitable for all.